Make Wall Street Pay Reparations

Our Mission

We are coming for the parasitic capitalist billionaires who have built their fortunes on the stolen wealth, labor and resources of African people in the U.S. and around the world! These criminals are getting away with murder, literally. But not for long. We call on the white community to join this movement under the leadership of the African Revolution as a revolutionary stand for social and economic justice.

We Demand:

The Wall Street bankers, corporate CEOs and capitalist elite must pay reparations to the black community inside the U.S. and around the world for their history and ongoing profiting from the enslavement, imprisonment and colonization of African people and the theft of their resources.

The 43,000 millionaires who received a $1.7 million tax break from the CARES Act must turn those resources over as reparations to the African community. They should make their checks out to the African People’s Education and Defense Fund, earmarked for the Black Power Blueprint Project in St. Louis, Missouri, the visionary, economic program of the African liberation movement.

Join the campaign to ignite a political firestorm to demand reparations from the moneyed sector of parasitic capitalism who are profiting from the colonial COVID-19 pandemic, raking in trillions of dollars from government bailouts while African people are dying at genocidal rates.

Make them pay!

Reparations Defined

What do we mean by “reparations”?

Reparations is not a favor, an act of charity or a payoff. We are demanding for the moneyed sector of parasitic capitalism to pay reparations to the African community through a substantial capital infusion into the Black Power Blueprint project in St. Louis, Missouri, one of the many economic development programs of the African People’s Education and Defense Fund, a 501c3 non-profit organization led by the black working class.

The Black Power Blueprint is spearheaded by Ona Zene Yeshitela, the President of the African People’s Education and Defense Fund. It is a multi-faceted development initiative that has encompassed the renovation of an abandoned building into a vibrant community center, the creation of a black community marketplace, and a community garden.

Plans for a basketball court, a community commercial kitchen and more are in the development stage. It is a positive response to gentrification, based on the principle of African self-determination, political and economic power in the hands of the African working class.

Wall Street Exposed

Wall Street was built on slavery and genocide.

In his book An Uneasy Equilibrium: The African Revolution Versus Parasitic Capitalism, Chairman Omali Yeshitela posed the question:

“Would capitalism and the resultant European wealth and African impoverishment have occurred without the European attack on Africa, its division, African slavery and dispersal, colonialism and neocolonialism?”

To which he answered, “No! No! No! and a thousand times no!”

The Chairman’s insightful analysis exposes the origins of the wealth of Wall Street, the symbolic and literal economic headquarters of parasitic capitalism.

Chairman Omali Yeshitela’s political theory of African Internationalism shows that a diseased, war-like and feudal Europe rescued and consolidated itself through assaulting and invading Africa, enslaving African people and committing genocide against the Indigenous people of the Americas.

As the Chairman has written:

“Capitalism was born in disrepute, of the rapes, massacres, occupations, genocides, colonialism and every despicable act humans are capable of inflicting.”

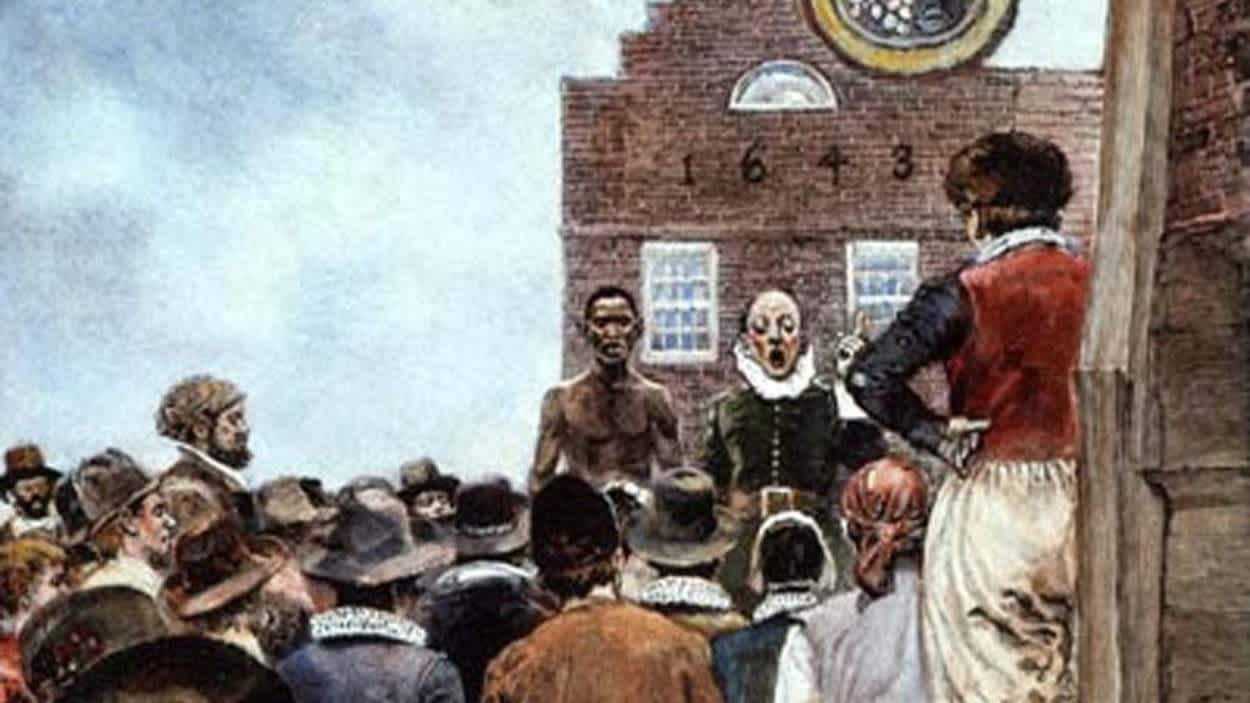

Obscured in the tall shadows cast by the skyscrapers of New York’s financial district is a brutal history of capture, torture and sale of African human beings. African people were forced to become the first commodities sold and traded to generate the start-up capital for the emergent colonial-settler enterprise known as the United States.

Although most depictions of African enslavement in the U.S. focus on the labor-intensive capitalism of plantation slavery in the American south, the exploitation of enslaved African people permeated every facet of the burgeoning U.S. economy. In other words, slavery was not a southern phenomenon. The hands of white colonizers in the north were also stained in blood.

New York was no exception.

Dutch and British colonizers enslaved African people in New York

The Dutch colonizers began forcing out and slaughtering the Indigenous people and stealing the land that was to be established as the “New Amsterdam” by the Dutch West India Company in 1625.

Enslaved African men were ripped from their homelands in Angola and Congo and forced onto ships to New Amsterdam.

Upon arrival, the Dutch slave masters forced the enslaved Africans into the bone-crushing labor of clearing land, building houses, and laying roads. Enslaved African women were kept in the households of the Dutch men who brutally raped them.

By 1650 New Amsterdam’s 500 enslaved Africans outnumbered those in Virginia and Maryland. By 1664 enslaved African people made up nearly a third of the population of New Amsterdam.

In late 1664, the Netherlands surrendered New Amsterdam to the British, officially establishing New York City. The trade in enslaved Africans intensified under British rule. The British trafficked thousands of chained Africans from the continent of Africa into its new colony.

According to an article published by the New York Public Library:

“Of the close to 4,000 people whose origins are known, 1,271 came from Madagascar, 998 from Congo, 757 from Senegambia, 504 from the Gold Coast (Ghana), 239 from Sierra Leone, and 217 from non-identified areas of the continent. With the aggressive increase in the slave trade and the expansion of the city, an official slave market opened in 1711 by the East River on Wall Street between Pearl and Water Streets. By 1730, 42 percent of the [white] population owned slaves, a higher percentage than in any other city in the country except Charleston, South Carolina. The enslaved population—which ranged between 15 and 20 percent of the total—literally built the city and was the engine that made its economy run.”

African people built the wall after which Wall Street was named

Chairman Omali Yeshitela made it plain when he spoke at the Occupy Wall Street gathering in Oakland, California in 2011:

“Wall Street was built by enslaved African people. The ‘wall’ was to protect the stolen land from the Indigenous people themselves.”

Just 50 meters from the site of New York’s first official slave market, the New York Stock Exchange was formed. The first “stock” traded on the stock market was African human beings.

The New York City Council announced the formation of the slave market, declaring that “all Negro and Indian slaves that are let out to be hired” would be “hired at the Market house at the Wall Street Slip.”

The first slave auction in New Amsterdam

Penny Hess, Chair of the African People’s Solidarity Committee (APSC), wrote in a 2009 article in The Burning Spear newspaper:

“Today stockbrokers discuss the price of oil over martinis at lunch. Two hundred years ago they talked about the price of a shipment of African people over a pint of ale.”

At least 20,000 bodies of enslaved Africans are buried in a cemetery in the heart of the financial district, on the corner of Duane Street and Elk behind the Ted Weiss Federal Building. At the urging of African activists, a granite monument was placed there in memory of the Africans whose lives were stolen to build the settler colony of New York. The burial ground wasn’t even publicly known until 1991 when builders broke ground on the Ted Weiss federal building and found hundreds of graves.

Wall Street’s enrichment off African oppression goes beyond chattel slavery

The scale of riches amassed by white New Yorkers from the labor of enslaved African people went far beyond the localized sale and rental of African slave labor. From the very beginning, New York’s financial industry as a whole rose to towering heights through profits of slavery.

First Dutch and then English colonizers built the city’s local economy largely around supplying ships for the trade in African people and the products of their labor: sugar, tobacco, indigo, coffee, chocolate, and cotton. New York ship captains and merchants bought and sold African people along the coast of Africa. Every white businessman in 18th-century New York had their hands in the slave trade.

During the period of chattel slavery, New York received 40 percent of U.S. cotton revenue through money earned by its financial firms and insurance companies.

Enslaved Africans toiled on the cotton, sugar, and tobacco plantations in the south. The crops were then sent to Europe or to the northern colonies and converted into finished goods. The sale of those goods was then used to fund more “voyages” to Africa by the white colonial slave drivers to kidnap more Africans and ship them to the Americas. This parasitic transactional relationship, with African oppression as its cornerstone, has been characterized as the “Triangular Trade.”

In the 19th century, U.S. banks in the north sold securities to help fund the expansion of southern plantations. The banks sold insurance policies to protect slave masters against the risk of boat capsizing or loss of “property” in the form of African people dying or becoming injured.

Some of the biggest insurance companies in the United States, including New York Life, AIG, and Aetna, cut their teeth selling insurance policies to slave owners.

By the mid-nineteenth century, raw cotton accounted for the majority of U.S. overseas shipments. What wasn’t exported was sent to fabric mills in northern states including Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

The impetus for the so-called industrial revolution, in which the fabric mills of New England played an instrumental role, was the supply of cotton produced by enslaved African people in the south. Brooks Brothers wouldn’t exist without cotton picked by enslaved African hands. Nor would Domino’s Sugar have become the largest sugar refiner in the country without the sugar cane made available by back-breaking, torturous African slave labor. The trains used to move goods farmed by enslaved Africans from the south to the northern cities traveled on railroads also built by enslaved African people.

Caesar, an African man who was enslaved in New York.

The banking industry took enslaved African people as “collateral” for loans

The southern plantation owners who made massive amounts of money off the work of the enslaved African people deposited that cash into banks that formed the corps of the Wall Street banking industry that we know today. U.S. banks accepted deposits from slave owners and counted enslaved African people as “assets” when assessing their customers’ wealth.

In 2005, JP Morgan Chase (the biggest bank in the U.S) admitted that two of its subsidiaries–Citizens Bank and Canal Bank in Louisiana– took enslaved Africans as “collateral” for loans. This means that if a plantation slave master defaulted on a loan payment, the banks would take ownership of their enslaved Africans.

Citibank, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo also benefited from slavery.

The predecessor bank of Citibank was founded by a sugar trader who financed the illegal slave trade importing Africans into Cuba in the 1800s. When Moses Taylor died in 1882, he was one of the richest men alive, with an estate worth $70 million, or $1.6 billion in today’s dollars.

As APSC Chairwoman Penny Hess continued in her 2009 Burning Spear article:

“The abolishment of the official trade in African human beings did not end white society’s dependence on the exploitation of forced African labor. The imperialist extraction from African people today is far greater than it was during the time of chattel slavery. The U.S. outlawed the importation of African people ended in 1808, but the trade continued with African people smuggled in as contraband. Additionally, plantation owners began to ‘breed’ African people. Forcing African men and women together in hideous dungeons called ‘breeding pens,’ one Virginia slave owner boasted he had sold 6,000 African children bred under these inhumane conditions.”